“BEEP BEEP BEEP,”

Your alarm goes off yet again. You’re feeling exhausted, unable to open your eyes. Rolling over your fingers hit the snooze button instantly, it’s a reflex by now.

As you roll over and lay back down to fall asleep your inner dialogue begins the usual debate every morning you set your alarm to get up and work out.

“You need more sleep.”

“No, get up!”

“Your body could use the rest.”

“No it doesn’t, you’ve been slacking too much.”

“But my bed is so warm and cozy.”

“You know you’ll be upset with yourself if you don’t get up.”

“I could work out later.”

“You always say that, but you know you never do.”

All of this back and forth conversation is essentially wasting time where you could be getting up and forcing yourself out the door to workout OR even going back to sleep.

I know I have this inner dialogue battle with myself, especially when for my 5 am workouts. The colder and darker the mornings become, the harder it is, especially With fall approaching. If you struggle with this inner dialogue battle as well below are 4 tips and tricks to continue or start your habit of waking up to your alarm clock, getting out of bed, and hitting the gym.

______________________________

1) BE PREPARED.

~ Make sure that you are well prepared so that you do not have any reason to climb back into bed. Have your workout clothes set beside your bed ready to be thrown on, or better yet go to bed in the clothes you want to work out in! I often do this and it serves as a reminder to get my butt out of bed because otherwise if I sleep in I wake up in my workout clothes and the guilt creeps in.

~ If you are like me and need your coffee in the morning, set it to auto brew so that as soon as you wake up your coffee is fresh and hot for you to drink a cup or fill up a mug on your way out the door. This saves a lot of time and assists me in getting up knowing that I have my hot coffee waiting for me.

~ Know what workout you’re going to do beforehand. When you wake up your mind can be groggy and having to decide on a workout is hard to do. If you have it prepared and ready to go from the night before it’ll take less mental strength that you can save throughout the workout.

2) CREATE AFFIRMATIONS.

~ These powerful and positive statements will help you battle the negative self-talk. Write out affirmations such as, “You Got This!” “You Have Goals.” “Win the Day” to serve as reminders to get up and win your morning the best you can. It’ll boost your motivation and provide statements to overcome the other thoughts that are tempting you to stay in bed.

~ Memorize self-affirmations so that when the negative self-talk kicks in you can talk back to it in your mind. Repeat these statements over and over until it is powerful enough to get you up and moving.

3) CHANGE/MOVE YOUR ALARM.

~ I recently have been struggling to get up and created a bad habit of shutting off my alarm instantly without thinking. I realized that the alarm sound just wasn’t doing it for me. I listened to several other options and decided on a different alarm that is longer and starts off quietly while gradually getting louder so that I am not jolted awake in annoyance and attempt to turn it off right away. This way I wake up more slowly and relaxed to start off my day.

~ Mornings that I can’t risk sleeping in, such as when I teach a morning class, I will also set my alarm on my Fitbit tracker. I love doing this because my tracker will vibrate on my wrist, which is a for sure way to wake me up.

~ Move your alarm clock/phone across the room. This will force you to get up and move if you want to snooze your alarm and sleep in. 9 times out of 10 when this happens I end up staying up since I already am out of bed and am less likely to crawl back into bed.

4) REWARD YOURSELF.

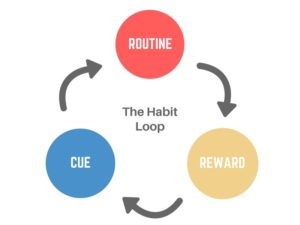

~ I recently read the book The Power of Habit and it discusses the habit loop, which is how habits are created. First, there’s a cue that causes you to follow through with your routine then you receive your reward. If your habit is to hit the snooze button and not get out of bed, figure out what reward you are getting from that routine. Whatever the reward is you have to provide the same reward when you do your new routine in order for it to stick. Maybe the reward is more sleep or being able to have a relaxing morning. To change your habit to working out in the morning and to gain the same reward maybe you need to go to bed earlier to get more sleep, or workout early enough where you have time afterward to relax and watch the news, read, or whatever it is you want to do. Identify the reward of snoozing your alarm and make sure you reward yourself after your new routine.

____________________________

Remember to show self-compassion as well.

There will be days that you won’t get up and that you need more sleep. Recovery is important as well. Some weeks you’ll rock at getting up and working out, others may be a struggle.

Just remember that each morning is a new chance to win the day. Do your best to stick with your new routine and it’ll become a habit sooner than you know!